This is an exhibition worth seeing to have a different insight on the war and of the desire for life that only war can make you feel.

"They don't look like war pictures; they rather look like Heaven, a place I am becoming very familiar with."

Stanley Spencer, 1923.

Convoy Arriving with the Wounded

213.4 x 185.4 cm

The narrative sequence of Spencer's canvases from the Sandham Memorial Chapel begins with Convoy Arriving with the Wounded. An open-topped bus forces its way through rhododendron bushed to the gates of the Beaufort Military Hospital in Bristol, which Spencer described as being 'as massive and as high as the gate of Hell'.

The unpleasant-looking gatekeeper adds an ominous element to the wounded soldiers' arrival. The keys at his belt belong to the chapel rather than the hospital, thus visually connecting the painting with its location.

Scrubbing the Floor

105.4 x 185.4 cm

In the first of the smallar, predella canvases painted for the chapel, a shell-shocked soldier lies prostrate in a dark hospital passageway while he obsessively scrubs the floor with a soapy rag. Above him figures rush back and forth with trays of bread. Spencer would sometimes envy the repetitive, insular lives of the asylum patients at the Beaufort Hospital, saying, 'I would like to do things that way... I could contemplate. Nothing would disturb me'.

Ablutions

213.4 x 185.4 cm

A sense of calm activity fills this everyday scene of a bathroom at Beaufort, busy with soldiers cleaning, drying themselves, dressing and, in the case of the man at the centre of the canvas, having iodine painted onto a wound. The detailed depiction of the sponge seen below the orderly cleaning taps, as well as the towels and the soap suds in the soldiers' hair, shows Spencer's fascination with painting different materials and surfaces.

Sorting and Moving Kit-Bags

105.4 x 185.4 cm

Orderlies sort the kit-bags belonging to a newly arrived convoy of soldiers in a bleak courtyard - a part of the Beaufort Hospital that, in essence, survives to the present day. Spencer wrote about the scene, remembering that, 'immediately on arrival at the hospital the kit-bags of the soldiers just arrived would be stacked all together in the courtyard... The orderlies would then carry them to wherever the patient wanted them, or open them if so required. They were all padlocked'.

Kit Inspection

213.4 x 185.4 cm

Soldiers struggle to flatten out the blankets onto which their kit is to be laid out prior to inspection. A humorous touch is provided by the one soldier who is near to completing his task, who appears awkwardly sprawled out as if he has fallen asleep on top of his kit. Kit Inspection is the only one of the chapel canvases to be set at Tweseldown, the camp near Farnham in Surrey, where Spencer was sent to train before he left for the Macedonian front.

Sorting the Laundry

105.4 x 185.4 cm

The laundry at Beaufort was a space where Spencer found respite from unwelcome chores. In this cheerful scene, a nurse supervises orderlies who sort through bags of laundry, including towels, jackets and sheets. A giant pile of white sheets builds up against the wall - a second pile, of spotted red handkerchiefs belonging to the permanent inmates from the asylum at Beaufort, reminds the viewer of the hospital's dual purpose during the war.

Dug - out (or Stand-to)

213.4 x 185.4 cm

Dug-out is the first in the narrative sequence of the Sandham canvases to depict a scene set at the Macedonian front. Soldiers in two trenches prepare their equipment for a 'stand-to' order about to be given by their sergeant, whose uniform is camouflaged by fern fronds. A tense, sombre atmosphere is created by the piles of barbed wire that appear like black thunder clouds, and by one of the soldiers looking ominously towards the right, which in the chapel is where Spencer's altarpiece of the Resurrection of the Soldiers appears.

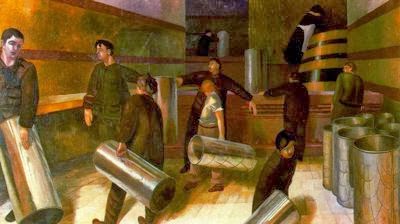

Filling Tea Urns

105.4 x 185.4 cm

Orderlies fill urns with tea to take back to the various military wards at the Beaufort Hospital, while a small figure behind a counter in the far background represents someone filling an urn for one of the asylum wards. Spencer was curious about the lives of the mental patients, who were housed in a separate wing, and he saw the counter as the dividing point in the hospital, that separated the patients into two distinct worlds.

The Resurrection of the Soldiers

640.5 x 526 cm

This is Spencer's vision of the end of the war, in which heaven has emerged from hell. Each cross amongst the astonishing and brave tumble across the canvas serves as an object of devotion (some of which are handed to Christ, who has been unconventionally placed in the mid-background); or marks a grave from which a soldier emerges; or serves to frame a bewildered face. The central motif is a pair of fallen mules, still harnessed to their timber wagon. The position of the cross on the altar in the chapel was of great importance to Spencer, for he felt it 'imperative that the top of the alta should be slightly above the bottom of the big picture' so that it might be incorporated visually amongst the mass of his own painted crosses.

Reveille

213.4 x 185.4 cm

Reveille (the morning wake -up) shows soldiers looming into the tent, announcing the fact that the was is over. In the chapel itself, the Resurrection has already taken place in the narrative sequence. Soldiers are shown dressing under mosquito nets, with malaria-infested mosquitoes hovering above them. Spencer had suffered from malaria whilst serving in Salonika, and it is probable that Harry Sandham, the dedicatee of the chapel, had died of complications related to the same disease.

Frostbite

105.4 x 185.4 cm

This scene at Beaufort Hospital is one of the busiest canvases in the chapel. Medical orderlies are shown bustling around patients, one of whom is having his feet scraped, which was one of Spencer's tasks. One of the orderlies has even sprouted angelic 'wings' in the form of the buckets that he carries.

Whilst at Beaufort, Spencer was introduced to the Confessions of St Augustine. He advocated that busyness brought one closer to God. Spencer used this philosophy to help him during his time at the hospital.

Filling Water-Bottles

213.4 x 185.4 cm

The orderly's 'wings' in Frostbite are echoed here in a different form - in the dramatically flowing 'wings' of the soldier's mackintoshes, as they collect water from a spring. The technical skill evidenced here demonstrates how Spencer had matured during his painting of the chapel canvases, for this was one of the last scenes he painted. Spencer has written about water fountains like this one, with "a great crowd of men round a Greek fountain or drinking-water trough (usually two slabs of marble, one set vertically into the side of a hill, having a slit-shaped hole in it which the other slab fits...)"

Tea in the Hospital Ward

105.4 x 185.4 cm

Tea-time must have been one of the highlights in the daily routine at the Beaufort Hospital. The contemplative figure in the bottom left-hand corner suggests that it was a quiet time, although a photograph in the Glenside Hospital Museum shows a reality quite different from the cosy scene evoked by Spencer, with formal, serried ranks of patients sat at trestle tables. This scene did not feature in Spencer's original scheme and was the last of the predella canvases to be painted in 1932.

Map-Reading

213.4 x 185.4 cm

The officer is the only soldier in command represented in the cycle. He is shown holding a map of Macedonia, on which Spencer noted all the places that he could remember visiting there. The soldiers in the background are shown feasting on bilberries, in a landscape that might almost be his home town, Cookham. The rendering of landscape and greenery typifies Spencer's skill at painting landscape and still-life, reflecting the rhododendrons by the Beaufort gatehouse in Convoy Arriving with the Wounded, and the rolling landscape above the Resurrection.

Bedmaking

105.4 x 185.4 cm

This seems a quintessentially English scene, with the mismatched fabrics, stripy wallpaper, and pin-ups above the bed (both Hilda and Spencer's father are shown). It has been suggested that the scene shows a hospital ward in a requisitioned house in Salonika, but it is more like to be a fusion of memories of Beaufort and Macedonia, where Spencer had been a patient himself. A figure - perhaps Spencer himself - is cocooned inside his blankets, but unlike his companions in Frostbite, he is upright, his expressive, oversized toes dancing on the urn-like form of the hot water bottle.

Firebelt

213.4 x 185.4 cm

The creation of a fire belt entailed the burning off of grass around the camp in order to create a protective fire barrier; here the soldiers are using copies of the Balkan News as firelighters. 'Of the last three arched pictures, I like [this] the best' Spencer wrote to Mary Behrend. The tangle of pulleys and complicated interplay of figures, including a Stanley-esque figure in uniform, holding a tent pole, does indeed make for a complex, but resoundingly successful composition.

Washing Lockers

105.4 x 185.4 cm

This ritual of scrubbing bedside lockers at the Beaufort Hospital took place in the bathroom of Ward 4. This duty was often overseen by the fearsome Sister Hunter, who once caught Stanley's brother, Gilbert, cleaning the floor with a mop instead of a scrubbing brush. 'There are no corners to Spencer's Ward', she admonished. Spencer shows himself squeezing himself between the bath tubs, where he was able to find some all-too-elusive personal space. For him, this menial task - like scrubbing floors - assumed a spiritual quality.

Sandham Memorial Chapel

"I had buried so many people and saw so many dead bodies that I felt that death could not be the end of everything."

Stanley Spencer, 1927

No comments:

Post a Comment