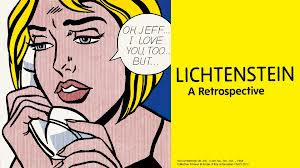

During one of my last weekends in London, I had the pleasure to attend: Lichtenstein A Retrospective held at the Tate Gallery, which closed on the 27th May.

For those of you who have never had the chance to meet Roy Lichtenstein's work I would define him as an Artist, in first place, and as the most influential figure in the American pop art. But, as you move on, reading this post, bear in mind: Lichtenstein was never ONLY the comic strip painter.

In Alastair Sooke's essay called Roy Lichtenstein: how modern art was saved by Donald Duck the author defines Lichtenstein's path, and recalls his wife's words, after his first pop work came out (Look Mickey, 1961):

"It didn't look like art."

Maybe not, but - as far as we knew - no one else was doing it. At last, the stumbling uncertainties and false starts of the Fifties were finished. He'd found his 'voice'.

(p. 17)

The Exhibition was divided into 13 sections, each of them representing a motif, and period in the artist's career, I will present some of the paintings and sculptures included in the exhibition through the analysis contained in the retrospective's booklet:

1. Brushstrokes

"Lichtenstein's pop Brushstrokes are usually seen as parodies of abstract expressionism, the movement that dominated American art in the 1950s. Unlike the emotionally charged, slashing strokes of Jackson Pollock or Willem de Kooning, Lichtenstein did not present the brushstrokes as the spontaneous expression of the artist's feelings, but rather as the result of a controlled act.

Little Big Painting 1965 features the quintessential artistic gesture through an industrial, almost automatic style: he turns attention from the action of painting to its unemotional description. 'Brushstrokes in painting convey a sense of grand gesture,' Lichtenstein said. 'But in my hands, the brushstroke becomes the depiction of a grand gesture.'

In the sense that we are not seeing real brushstrokes, but their dispassionate representation, this and other paintings such as Brushstroke 1965 an Brushstroke with Spatter 1966 are a declaration of intent. The irony is that Lichtenstein avoided photographic techniques to recreate the mechanically reproduced image of the brushstrokes and decided instead to paint them by hand."

2. Early Pop

"In the 1950s, Lichtenstein struggled with an abstract expressionist style to find his own identity as a painter. Towards the end of that decade, he started to experiment with cartoon imagery, immediately setting up a dichotomy between artistic form and popular commercial content. By 1961 he had begun to incorporate into his paintings imagery from popular culture, such as comic books and advertisements clipped from newspapers and telephone books.

Look Mickey 1961 was a breakthrough for the 37-year-old Lichtenstein and set the course of his career. Based on an illustration from Donald Duck Lost and Found 1960, a Little Golden Book owned by Lichtenstein's sons, it is considered his first pop painting (though it was not exhibited publicly until 1982). He made his rendering look like the cheapest of funnies, right down to its mimicry of three-colour printing, poor registration (the areas of colour do not quite fit together) and half-tone dots. Faint pencil lines show Lichtenstein adjusting pose and composition. Never in his life a straight copier, he sought to bring and aesthetic and formal order to his sources.

Other early works feature deadpan renditions of visual ads. They depict objects manipulated by disembodied female hands, such as Sponge 1962 or Spray 1962, suggesting the portrayal of women as an extension of the household appliance in America's consumer culture.

Alongside Andy Warhol, Claes Oldenburg and other American pop artists, Lichtensteins's work explored the potent collision of commercial and fine art. What the critic Roland Barthes wrote of pop art in general applies to Lichtenstei in particular: 'There are two voices, as in a fugue. One says: "This is not art"; the other says, at the same time, "I am Art."

3. Black and White

"Lichtenstein used a black-and-white palette in this series of paintings of everyday functional objects. Yet the sources he drew from for Tire 1962 and Ball of Twine 1963 were not the objects per se, but stark graphic renderings that he adopted from anonymous illustrations in newspapers and mail-

order catalogues.

His restricted palette laid bare the reductive nature of commercial images. Do those jagged lines really depict a tyre tread? Lichtenstein's versions, enlarged and sharply defined - 'islanded' in the centre of the canvas - are simultaneously abstract images and graphic delineations of objects.

He also explored another approach, filling the entire canvas with the image to achieve an exact fit between the work and its subject. In Portable Radio 1962 and Compositions I 1964, he noted, 'the painting itself can be thought of as an object'.

Lichtenstein initially made his own stencils by drilling holes through strips of aluminium to apply dots on the painting. The inking was uneven anMagnifying Glass 1963 metaphorically plays with the enlargement of these dots and reveals another strategy of pop art: subverting the scale of objects.

Lichtenstein initially made his own stencils by drilling holes through strips of aluminium to apply dots on the painting. The inking was uneven anMagnifying Glass 1963 metaphorically plays with the enlargement of these dots and reveals another strategy of pop art: subverting the scale of objects.d the small perforated screen had to be moved several times, resulting in blurring and other unintended marks. In 1962 he began to use larger, prefabricated Benday screens that enabled him to create more even and uniform patterns.

4. War and Romance

"Soon after New York dealer Leo Castelli proposed to represent Lichtenstein in 1961, the artist turned to two subjects that would make him famous: war and romance. These iconic pop paintings became an overnight success, yet they also provoked some virulent reactions in the cultural world.

In 1964 Life magazine facetiously queried 'Is he the worst artist in the US?' - a question that riffed on a headline 15 years earlier in a 1949 Life magazine feature on Jackson Pollock which asked laconically: 'Is he the greatest living painter in the United States?'.

Based on comic books such as All-American Men of War and Girls' Romances, the war and romance paintings explored melodramatic stories and clichéd gender roles as disseminated through American mass media, including film. Such choices reveal Lichtenstein's interest in the 'pregnant moment' - the crux from which one can imagine the whole story.

Dramatic close-ups of female faces such as Drowning Girl 1963 or Hopeless 1963 feature women in states of distress or reluctant acquiescence. The war paintings are dominated by violent action and scenes of discharging weapons. In Bratatat! 1962 a male fighter stares vehemently at his target; in other paintings, the explosions stand alone.

Whaam! 1963 reveals how Lichtenstein carefully reworked his source image by cropping, eliminating detail, deleting or editing speech bubbles and making the rocket trail horizontal rather than diagonal, thereby sharpening the drama and giving more weight to a single enemy. The result is not just the story of a dogfight, but a compositional tightrope act. 'I was interested in using highly charged material [in] a very removed, technical, almost engineering drawing style', Lichtenstein said."

5. Landscapes/Seascapes

'Art relates to perception, not nature,' Lichtenstein once stated. In his series of Landscapes 1964 - 7, the placid emptiness and subtle restraint of each work seems a far cry from the frenzied melodrama of the war and romance paintings, even if a couple of them, such as Sunrise 1965, are derived directly from the background of a comic strip frame.

These land - and sea-scape works are pared down to a series of horizontal lines that represent the essential elements of sky and sea, marked by strips of cloud or rippling waves. The near absence of subject matter and

almost abstract scenes freed Lichtenstein to experiment with materials and optical effects.

Sea Shore 1964 was painted onto layered sheets of Plexiglass that add a sense of depth. The artist found another kind of optical excitement in Rowlux - sheets of moulded biconvex plastic that create the illusion of an unstable, shifting surface when viewed from different angles. Seascape and Pink Seascape (both 1965) incorporated Rowlux, about which Lichtenstein explained, 'these pieces of plastic seemed perfect for sky and water, [which] move or change their appearance constantly as you look at them.' Such works are also a nod to the dazzle of Op art (Optical art), which made its debut in 1964.

Three Landscapes 1970-1, Lichtenstein's only venture into film, was commissioned by the Los Angeles County Museum of Art for the exhibition Art and Technology. Lichtenstein produced a three-screen 35mm film loop installation describing a marine landscape - the bottom half of each film showed the ocean rippling in the sunlight, while the top half depicted the sky in three still images.

6. Modern

"Lichtenstein grew up in New York City in the 1930s, the heyday of art deco, so the sleek lines and decorative panels of landmarks such as the Chrysler Building 1930 and the Empire State Building 1931 were familiar to him. When in 1966 he was commissioned to design a poster for the city's Lincoln Center, he turned his focus backwards 30 years to use an outmoded architectural art deco style as the basis for the poster.

This was the starting point for a series of paintings and sculptures that he called his Modern series. While much of his art derives from specific sources, these works refer to a design style. Lichtenstein was fascinated with art deco's merging of ornamentation and mass production, but he also humorously described it as 'Cubism for the home': he felt that it had domesticated Picasso's radical reshaping of our perception.

'The geometric logic of art deco [seemed] too easily to fit the instruments, the T-squares and compasses, of the designers and architects,' he said. 'I saw in it a too-rational quality that had an absurd twist.' The artist played around with modern motifs as a pure exercise on style. For example, Modern Painting Triptych 1967 explores a modular geometric pattern that can be repeated sequentially to create a decorative panel.

The brass sculptures Modern Sculpture 1967 and Modern Sculpture with Velvet Rope 1968 are also original compositions where the artist paraphrases architectural details and furnishings, such as doorways and railings, commonly found in the interiors of New York skyscrapers, film theatres or auditoriums such as Radio City Music Hall. Lichtenstein clearly enjoyed the absence of a specific model, which allowed him to improvise freely in an abstract, almost musical manner. He was a jazz fan and amateur musician, who studied saxophone in his last years."

7. Art about Art

"In parallel to his work inspired by the contemporary visual culture of comic books and advertising, Lichtenstein began an ongoing dialogue with the artists of the past. Whether through appropriation, stylisation or parody, these singular works engage with art historical styles, such as impressionism, futurism and surrealism, or target the paintings of artists like Picasso, Matisse and Piet Mondrian. As a group, they result in vivid recreations that herald Lichtenstein's ultimate subject: art about art.

In some cases, Lichtenstein appropriated a landmark painting such as Emanuel Gottlieb Leutze's Washington Crossing the Delaware 1851 or Claude Monet's Rouen Cathedral series 1892-4 and rephrased the original work in his own visual language. In others, he worked with the stylistic conventions of a movement or a genre, such as the still life or Native American motifs, to create original compositions.

Lichtenstein, who emphatically stated that 'the things that I have apparently parodied I actually admire', regarded Picasso as the 'greates artist of the 20th century' and openly acknowledged how much he had learned from him. In Femme d'Alger 1963 Lichtenstein translated Picasso's Women of Algiers 1955 (itself based on an 1834 painting by Eugène Delacroix) into the pop idiom, transforming a high-art painting 'into another high-art medium that pretends to be low art.' "

8. Artist's Studios

"Lichtenstein painted four monumental paintings for his Artist's Studio series from 1973-4. Three of these are reunited in this exhibition for the first time since they were exhibited in New York in 1974.

These large, complex compositions incorporate a myriad of iconographical elements. Inspired by Henri Matisse's two 1911 paintings Red Studio and Pink Studio, Lichtenstein similarly conceived each of his own Artist's Studio paintings by representing a partial inventory of his own paintings. Taking the opportunity to rephrase many of his earlier works, Lichtenstein also added a direct reference to Matisse's masterpiece The Dance 1909.

Lichtenstein's own paintings were so widely disseminated and reproduced by the mid-1970s that they had achieved a level of stylistic familiarity that a general public would instantly recognise.

This enabled him to appropriate his own work in the same way as works by other major artists. For instance, Artist's Studio 'Look Mickey' 1973 features his iconic early work rendered almost to real scale. Other details or items of furniture have similarly been borrowed from previous works such as a telephone from R-R-R-R-Ring!! 1962 and a sofa from Couch 1961."

9. Mirrors and Entablatures

Throughout his life, Lichtenstein consistently returned to issues of vision and perception. In the late 1960s he studied the pictorial conventions for representing mirrors and reflections in commercial catalogues. He also photographed real mirrors, tilting them under different sources of light to understand their effects.

The paintings that followed presented coded renderings of mirrors where reflections are conveyed through an intricate composition of Benday dots. By 1972, Lichtenstein had painted almost fifty versions in different shapes: circular, oval, rectangular. Ever since Leonardo da Vinci called the true artist a 'mirror of nature', mirrors have symbolised painting itself, and their depiction within paintings has been a sign of the artist's mastery.

Entering this tradition, Lichtenstein turns it on its head while retaining its essential painterly quality. As in some of Lichtenstein's earlier black and white 'object-paintings', each mirror, each object, fills the canvas, creating a mock trompe l'oeil that fools nobody's eye - and which produces no real reflections except depicted ones that lie on the surface as paint.

Lichtenstein described the Entablature as a 'Minimalist painting that has a Classical reference'. In ancient architecture, the entablature was a supportand decorative band at the top of a column. However, rather than look at examples from Greece or Rome, Lichtenstein was interested in the way the motif had been appropriated and evolved in modern America, particularly as a symbolic carrier of statehood and capitalism. Unusually, he based the paintings on photographs that he himself had taken of institutional buildings around Wall Street, New York's financial centre."

10. Perfect/Imperfect

The Perfect/Imperfect series is a relatively unknown group of works, which explore the vocabulary of abstraction with geometric fields of colour that challenge the edges of the traditional canvas.

Lichtenstein made the Perfect paintings by drawing a line, following it along the canvas and returning to its starting point. He then filled in the demarcated geometric spaces with areas of flat colour, dots or diagonal lines.

The Imperfect paintings provide a playful variation on the same method: 'The line goes out beyond the rectangle of the painting, as though I missed the edge somehow,' Lichtenstein explained. To accomodate those deliberate creative errors, the Imperfect paintings include a triangular protuberance attached to the canvas that expands the painting beyond its rectangular frame and into the world of the viewer.

While the Perfect/Imperfect series was Lichtenstein's most sustained incursion iinto the realm of abstraction, he also acknowledged it as a form of parody: 'It seemed to be the most meaningless way to make an abstraction... the nameless or generic painting you might find in the background of a sitcom, the abstraction hanging over the couch.' "

11. Late Nudes

"Late in his career, in the mid-1990s, Lichtenstein broached one of the most ancient genres of art, the nude, returning to the female subject in a new and provocative way.

Unlike many artists, Lichtenstein did not use live models for his depictions of the female body; instead he returned to his archive of comic clippings to select female characters as subjects - and then literally undressed hem, by imagining their bare bodies under their clothes before painting them as nude.

The paintings Nudes with Beach Ball 1994 and Blue Nude 1995 are examples of his late approach to the nude, brought together at a huge scale in original compositions of single, double and group portraits. The result is a disturbing violation of conventions. The noble nude has been rendered as erotic graphic pulp; the paintings propose her large schematic bland body as an object of desire, yet she experiences desire as well, often captured in a state of reverie or bliss. Like Picasso and Matisse before him, Lichtenstein's fascination with the painter/model relationship reaches a new level of intimacy and sensuality meshed with the formal concerns of his painting.

The female presence is ambiguous, with Benday dots that break the conventions of chiaroscuro by overlapping and aliminating the fleshly contours of her bodyto blur the distinction between figure and background. The last work in the series, Interior with Nude Leaving 1997, announces both the departure of the figure and the arrival of a new visual language. Shading here is freed from contours and line has taken on colour in such a way that it renders space newly complex, while still staying true to the credo Lichtenstein had learned as an art student: 'Form is the result of unified seeing.' "

12. From Alpha to Omega: Early Abstractions and Late Brushstrokes

This room spotlights a group of early paintings from 1959-60, when Lichtenstein attempted to engage with abstract expressionism. These are rich and vivid experimentations with colour that marked a transitional period for the artist. Lichtenstein soon abandoned this painterly style in his search for his own pop vocabulary.

At the end of his life, the brushstroke re-emerged with surprising new meanings. In 1996 he embarked on a little-known series of small paintings that he called 'obliterating brushstrokes', in which hand-painted, loosely applied brushstrokes are juxtaposed with geometric forms. In contrast to the monumental nude paintings made at the same time, they can be seen as a quiet, almost simple meditation on the very essence of painting. These small late paintings bring together two opposing approaches to painting - spontaneous release versus controlled application - via its very DNA: the brushstroke."

At the end of his life, the brushstroke re-emerged with surprising new meanings. In 1996 he embarked on a little-known series of small paintings that he called 'obliterating brushstrokes', in which hand-painted, loosely applied brushstrokes are juxtaposed with geometric forms. In contrast to the monumental nude paintings made at the same time, they can be seen as a quiet, almost simple meditation on the very essence of painting. These small late paintings bring together two opposing approaches to painting - spontaneous release versus controlled application - via its very DNA: the brushstroke."

13. Chinese Landscapes

"One of the dominant notes of Lichtenstein's late work is his fascination with the simplicity of Chinese art. In 1955 he returned to the landscape genre, creating more than 20 works in homage to the highly stylised paintings of the Song dynasty (960 - 1279 AD).

Given its emphasis on the calligraphic mark, luminous expanse and the relationship of man to nature, Chinese scroll painting offered both a challenge and a new direction for Lichtenstein's technique, which reaches new heights of sophistication. In Landscape with Philosopher 1996, he engages with a more complex system of applying dots (in some paintings there are as many as 15 different sizes of dots) to convey the atmospheric quality and subtle gradations of the original Chinese landscapes.

Landscape with Boat 1996 reflects a moment of serene abstraction in the latter years of the artist's life. As the illustrational aspects of his pop paintings start to recede, contour lines of figures fade away, and forms in space dissolve, Lichtenstein presents pure painterly delicacy in an almost cosmic vision true to the old Chinese masters he so admired."

Text by: Sheena Wagstaff and Iria Candela.

Absolutely one of the best exhibitions I have ever been too: interesting, complete, original, colourful, and thoughtful. I suggest the reading of the essay I mentioned at the beginning, to understand, especially, the contrast between form and content in Lichtenstein, and his being an artist.

As Alastair Sooke wrote:

"The paradox of Lichtenstein's self-portrait is that it is both anonymous and full of identity."

(p. 45)

.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment